The circular economy presents big opportunities for sustainable lighting. Zhaga, the global lighting industry organisation, discusses the needed standards to best position the lighting industry for these opportunities.

Reinhard Lecheler

One of the key challenges of the 21st century is the building of a sustainable society: one that can meet its own needs in a way that doesn’t compromise the ability of future generations to meet theirs. A key component to building such a society is implementing a circular economy.

A circular economy is an economic system that aims to limit the consumption of resources and materials and avoid landfilling waste. This can be supported by promoting serviceable products that use a modular design and that can be easily repaired, adapted, and upgraded.

In Zhaga, we use the term ‘circularity lighting’ for products and systems that support the aims of the circular economy through enhanced serviceability. Sustainable lighting is a more general term and includes the properties of circularity lighting next to supporting energy efficiency.

“Sustainable lighting systems are best built on an ecosystem of modular lighting products and services, including durable luminaires, LED modules, LED control gears, intelligent sensors, and communication modules,” says Reinhard Lecheler, Chair of the Zhaga Steering Committee, and author of a forthcoming white paper on circularity lighting.

With the circular economy and sustainability being key components to such important initiatives as the European Green Deal and its Circular Economy Action Plan, Zhaga is hosting an online summit on sustainable lighting, particularly as it relates to smart cities and buildings, on 29 September.

The Essential Role of Standardisation in Promoting a Circular Economy

Since its founding in 2010, Zhaga has been developing and standardising interface specifications for LED modules and control gear for lighting product manufacturers, lighting specifiers, and operators.

“The road to resource-efficient, circular business models starts with standardisation,” explains Dee Denteneer, Secretary General of the Zhaga Consortium. “By ensuring that these luminaires and components can be easily repaired, upgraded, replaced, or serviced, we’re futureproofing lighting and promoting a circular economy.”

ee Denteneer – Zhaga Consortium

Zhaga’s specifications are called Books, with each Book defining the interface of one or more components of an LED luminaire. All sensor/communication modules and luminaires designed and certified in accordance with a Zhaga Book are guaranteed to work together as intended, even if they come from different manufacturers. Taken together, the interface specifications established by the Zhaga Books enable an interoperable ecosystem of luminaires and components (e.g., communication and sensor modules, LED modules, control gear, etc.).

To illustrate what this looks like in practice, take the luminaires we use to light our offices, schools, industries, and streets, which are typically designed to ensure a long lifetime – up to 70,000 or even 100,000 hours. However, this longevity often means that the luminaire outlasts the connectivity solutions, which are subject to rapid technological change.

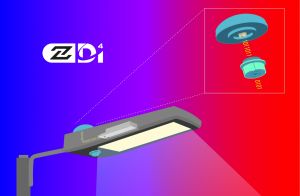

According to Lecheler, the communication protocols, sensor technologies, and functions can change during a luminaire’s lifetime, with completely new solutions emerging. Thus, it makes sense to decouple, or separate, the connectivity-related parts of a long-life luminaire from the rest of the luminaire. The way to do this is via a well-defined interface, such as those specified in Zhaga Books 18 for outdoor luminaires and 20 for indoor luminaires, and by enabling supplementation, upgrading, or replacement at any time after the luminaire is installed. Thus, the luminaire lifetime can be considerably extended.

The best-known use case for replaceable components is of course with old luminaires that fail. But it’s not just old luminaires that fail. Sometimes even a high-quality, durable luminaire might stop working early. For example, spontaneous defects or environmental influences (such as high surge voltages on the mains supply) can lead to a failure of the luminaire and/or its components. Such a failure is particularly problematic when, after years of operation, replacement luminaires and spare parts are no longer available, meaning the entire group of luminaires must be replaced.

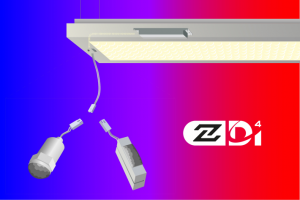

According to Lecheler, to prevent such situations, one can turn to Zhaga Book 21 and Book 26, which describe standardised interfaces of linear LED modules that can be professionally replaced on-site. If the luminaire and LED modules carry the Zhaga logo, one knows that its components are interoperable and work together as intended.

Book 18

Enabling Product Updates

Books 21 and 26 also address product updates. According to Lecheler, an LED luminaire’s energy consumption is primarily determined by the (LED) light source being used. While the efficiency of an LED module continuously decreases during its operating time, the technological development – and the efficiency of new LEDs – is constantly progressing. At a certain point, the efficiency gap between the old, installed LED module and a newer, more efficient one becomes so great that it simply makes sense – from both an energy and economic standpoint – to replace the module.

However, these replaced LEDs don’t necessarily have to end up in the landfill. Thanks in part to Zhaga’s standards, the old module can be taken out of the luminaire undamaged. It may therefore be reused for applications requiring short daily usage. Alternatively, its materials could be more efficiently recycled in a process specifically tailored to electronics.

“The ecosystem created by Zhaga Books 21 and 26 allows for the selection of modules with different application characteristics (colour temperature, CRI, etc.), which are clearly specified by the manufacturer,” says Lecheler. “The connectors defined in the books ensure that the upgrades can be carried out in the field.”

Book 20

Ensuring Interoperable Control Gear

In addition to luminaires, Zhaga also deals with the interoperability of LED control gear. A prominent example is the analogue LEDset interface, with which the output current of a control gear can be set in a simple and standardized way and thus individually adapted to the requirements of a lighting application. The somewhat more modern form of current setting via uniform NFC programmers was also specified by Zhaga, is widely used in the industry, and allows for an update of the settings of the LED control gear in the field

The next frontier in control gear interoperability involves electromagnetic compatibility (EMC). To ensure that control gear can also be replaced easily and in compliance with legal requirements from this point of view, Zhaga develops requirements and guidelines in coordination with the relevant EMC Standardization Development Organizations.

Lighting the Future

By creating standards that promote modularity and the interoperability of lighting systems, Zhaga is helping to ensure that luminaries are repairable, upgradable, replaceable, and serviceable. “As a result, we’re lighting the future and making the circular economy go round,” concludes Denteneer.

To learn more about Zhaga standards and their application to the circular economy, be sure to tune in on 29 September for Zhaga’s summit on Sustainable Lighting for Smart Cities and Buildings. This online summit will expand on the standards and topics covered in this article, with a specific focus on how they apply to the smart city and building sectors. Representatives from national authorities, cities, industry associations, and lighting design and manufacturers will share their thoughts on the latest regulations and what they mean for the lighting industry. The summit will also present pioneering use cases that illustrate Zhaga standards in action. Register here: www.zhagastandard.org/zhaga-summit.html.

Recent Comments